A good story doesn’t just describe a place—it moves you there.

You’ve likely experienced it yourself: one minute you’re scrolling your phone, the next you’re standing (in your mind) at the edge of a red gorge in Western Australia, or walking through early mist in a Tasmanian forest. That sensation—when words, visuals, and emotion blur into a kind of virtual presence—is what psychologists call narrative transportation.

It’s more than a poetic idea. Narrative transportation theory explains how deeply immersive storytelling can shift perceptions, influence decision-making, and even change long-held beliefs. For tourism, particularly in regional contexts where stereotypes and surface impressions can limit visitation, this is a powerful—and underutilized—tool.

Because most regional campaigns focus on features: scenery, food, logistics. But what makes people care—what makes them book the trip, tell a friend, or come back—is the story. When it’s told well, they don’t just learn about your region—they enter it.

This article explores how narrative transportation applies to regional tourism, and how it can be used not just to promote destinations, but to reshape the emotional maps people carry in their minds. Drawing on campaigns from New Zealand, Western Australia, and other storytelling-driven strategies, we’ll explore how to make people feel something before they arrive—and why that might matter more than ever.

What Is Narrative Transportation Theory—and Why Should Regional Tourism Care?

Narrative transportation theory was first formalised by psychologists Melanie Green and Timothy Brock in the early 2000s. Their research explored how stories can mentally and emotionally transport people into a narrative world. When someone becomes absorbed in a compelling story, they lower their cognitive defences, engage their imagination, and emotionally invest in the people and places described. This “transported” state isn’t passive—it can change attitudes, beliefs, and even behaviour.

For tourism, the implications are enormous.

Most destination marketing still operates on an information-based model: where to stay, what to eat, which trail to walk. But information alone doesn’t create emotional connection. And it certainly doesn’t reframe perceptions. What does? Story.

And not just any story—stories that draw people into a vivid experience. These might come as short films, podcasts, first-person travel blogs, or even place-based social media posts. The best of them follow the structure of classic narrative:

- a protagonist (guide, local, or visitor),

- a journey (physical, emotional, or both),

- tension or discovery,

- and a resolution that leaves the viewer changed.

When this structure aligns with real cultural and sensory elements of a region, the impact can be profound.

For regional Australia—where many towns battle outdated stereotypes or flat awareness—narrative transportation offers a pathway not just to attention, but to reappraisal. It invites potential visitors to not only see the region differently, but to emotionally enter it, even before the trip is booked.

And the best examples of this aren’t found in billboard slogans. They live in the well-told stories of real people, rooted in real places—narratives that feel so compelling, you forget you’re being marketed to at all.

Case Study: New Zealand – Stories That Shaped a Nation

When people think of destination marketing, they often think in visuals—beaches, mountains, food. But New Zealand’s most successful tourism campaign wasn’t built on scenery alone. It was built on narrative.

“100% Pure New Zealand,” launched in 1999, started as a clean, minimalist positioning. But what followed wasn’t just an ad campaign—it was a national storytelling project. Through tightly woven themes of purity, adventure, and myth, the country began to craft a story that transported viewers not just across the Tasman, but into a mental and emotional version of Aotearoa.

Key to this was the integration of:

- Cinematic storytelling: Films like The Lord of the Rings became narrative scaffolds—turning landscapes into mythic territory.

- Cultural depth: M?ori concepts like kaitiakitanga (guardianship of the land) weren’t just included—they were made central to the narrative.

- Character-driven marketing: Campaigns featured locals, adventurers, and seekers—not anonymous aerial drone shots.

Viewers didn’t just want to visit—they wanted to step into the story.

And it worked. New Zealand’s brand rose from near anonymity to global distinction. What’s more, the emotional tone of the campaign generated deeper visitor loyalty, stronger word of mouth, and richer engagement across multiple sectors—not just tourism, but education, migration, and investment.

The takeaway for regional Australia? You don’t need mountains or hobbits. You need a compelling, locally rooted story—told with enough clarity and emotion to allow others to walk inside it.

Where Narrative Falls Flat: The Common Pitfalls

Not all storytelling transports.

In regional tourism, there’s a growing recognition that stories matter—but a lot of what’s called “storytelling” is actually just rebranded promotion. It’s a highlight reel, not a narrative. And audiences can feel the difference.

Here’s where well-intended campaigns often miss the mark:

- No emotional core: A list of attractions, even beautifully shot, isn’t a story. Without a human anchor—someone to care about—there’s no emotional gravity.

- Over-polished, under-lived: When campaigns rely too heavily on stylised drone shots and scripted lines, they lose authenticity. Visitors aren’t looking for perfection—they’re looking for connection.

- Cliché over character: If every town is “vibrant,” “bustling,” or “hidden,” then none of them are memorable. Generic copy kills narrative immersion.

Narrative transportation requires risk. Vulnerability. Specificity. It means handing the mic to real people and letting the region speak through their lived experience. That’s where story stops being content—and becomes memory.

Case Study: Western Australia – Walking on a Dream

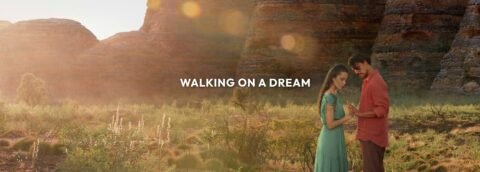

Among the more ambitious recent campaigns, Tourism WA’s “Walking on a Dream” stands out for its cinematic ambition and lyrical tone.

The campaign leans heavily on emotion, movement, and cultural resonance. It doesn’t deliver a list of experiences—it draws the viewer into a state. Indigenous performers guide the viewer across surreal WA landscapes: red dunes, floating salt lakes, whale-song oceans. The aesthetic is dreamlike, even spiritual.

The campaign leans heavily on emotion, movement, and cultural resonance. It doesn’t deliver a list of experiences—it draws the viewer into a state. Indigenous performers guide the viewer across surreal WA landscapes: red dunes, floating salt lakes, whale-song oceans. The aesthetic is dreamlike, even spiritual.

But beyond visual beauty, the storytelling attempts something deeper: to transport the audience into the feeling of being there. You aren’t being told what to do—you’re being invited into a myth.

Why it resonates with narrative transportation theory:

- It offers a shift in identity schema: WA is repositioned from a dry, distant resource state to a cultural, mysterious, and immersive environment.

- Human presence is subtle but symbolic: the characters are not tourists—they are cultural guides and stewards.

- The rhythm and mood override itinerary: this isn’t a story about planning—it’s a story about sensing.

That said, the campaign also highlights the trade-offs of high-production storytelling. Its ethereal tone may feel distant or abstract to some. Unlike more grounded, character-driven narratives (like Tasmania’s Off Season or NT’s Love Letters to Alice), “Walking on a Dream” places emotion over exposition, mood over message.

For regional towns, the lesson isn’t to emulate the aesthetic—but to recognise that emotional tone, cultural grounding, and story structure can create lasting impressions, even when plot is minimal. What matters is that the viewer feels invited—not just to visit, but to imagine themselves already inside the story.

Regional Australian Campaigns That Tell Stories, Not Just Sell

Across Australia, a quiet narrative shift is taking place. Increasingly, regional tourism campaigns are moving away from broad slogans and drone-shot montages—and toward stories that feel inhabited. These campaigns don’t always announce themselves as storytelling, but they invite viewers to emotionally enter a place, not just evaluate it.

Here are four notable examples of narrative strategies that reflect this shift—each offering different lessons in how narrative transportation can help reframe, revalue, and reconnect people with regional destinations.

Tasmania – “The Off Season”

Tasmania’s Off Season campaign doesn’t fight against winter—it embraces it. Instead of promoting warmth or escape, it draws the viewer into the mood of the island’s quieter months: log fires, thick mist, forest fungi, long dinners, silence.

Tasmania’s Off Season campaign doesn’t fight against winter—it embraces it. Instead of promoting warmth or escape, it draws the viewer into the mood of the island’s quieter months: log fires, thick mist, forest fungi, long dinners, silence.

Narratives are conveyed through implied moments: a couple paddling through dark water at dusk, a potter sipping wine under an old tin roof, a solo traveller journaling by candlelight. The characters are never fully explained—but they don’t need to be. The story is felt, not told.

Why it works:

- It builds an emotional setting, not just a physical one.

- It trusts the viewer’s imagination—less marketing, more mood.

- It’s grounded in local culture, not pasted on top.

For councils, this is a model of how tone, pacing, and voice can transport without overselling.

Northern Territory – “Love Letters to Alice”

This campaign tells the story of Alice Springs not through polished promos, but through personal letters—written by locals, addressed to the town itself.

This campaign tells the story of Alice Springs not through polished promos, but through personal letters—written by locals, addressed to the town itself.

These letters aren’t sweeping manifestos. They’re intimate. Reflective. One speaks of returning home. Another of raising kids. Another of learning to belong. Together, they form a mosaic of emotional attachment—inviting viewers to feel like they’re eavesdropping on something sacred.

Why it works:

- It uses authentic voice—the emotion is real, not manufactured.

- It invites the viewer to empathise, not just observe.

- The town becomes a character, not just a location.

A small town doesn’t need a big budget to tell powerful stories. It just needs trust in local voice.

South Australia – “For Those Who Want a Little More”

This campaign eschews a single story in favour of fragments—short visual vignettes that suggest depth rather than explain it. A quiet breakfast in the hills. A dance on a vineyard road. A whispered moment on the coast. The characters are barely named, but you feel their presence.

This campaign eschews a single story in favour of fragments—short visual vignettes that suggest depth rather than explain it. A quiet breakfast in the hills. A dance on a vineyard road. A whispered moment on the coast. The characters are barely named, but you feel their presence.

Why it works:

- It builds space for identification—viewers can see themselves inside the scenes.

- It uses poetry of pace—slow cuts, ambient sound, unresolved emotion.

- It reflects the complexity of place—not just what it is, but how it feels.

For regions with layered stories or emerging identities, this approach lets contradiction live inside the brand—without needing to resolve it.

What These Campaigns Share

While each campaign has a different voice, the ones that succeed at narrative transportation have key elements in common:

- Emotional sincerity—not just polished visuals, but something real.

- Human connection—a voice, a face, a memory that lingers.

- Narrative structure—even loose or abstract, they still follow a journey.

And perhaps most importantly: none of these campaigns try to be everything to everyone. They lean into specificity. And that, paradoxically, makes them more universally felt.

How Regional Towns Can Apply Narrative Transportation

Narrative campaigns don’t have to be big or cinematic to be effective. They have to be felt. And that starts by understanding how story works—not just as content, but as a psychological experience.

Here’s a framework councils and tourism planners can use to bring narrative transportation theory into practice—without needing a blockbuster budget.

Start with a Person, Not a Place

People don’t connect with locations. They connect with lives lived in them.

Choose a real human figure to centre the story. It might be:

- a third-generation cheesemaker,

- a young family who moved from the city,

- an elder sharing language and land,

- a seasonal backpacker working on a farm.

Let them speak in their own voice. Audiences remember people, not slogans.

Create a Journey—Even a Small One

Every good story follows a path. It can be modest:

someone arriving with doubt, discovering something unexpected, and leaving with a small shift in perspective.

This creates narrative movement—essential for transporting a viewer from passive watching into emotional presence.

Think of:

- A traveller who came for the wine and stayed for the community.

- A local who left and came back, seeing their town with new eyes.

- A visitor who came to switch off and ended up finding purpose.

Use Sensory and Spatial Language

Narrative transportation works best when people can feel themselves inside the story.

Let the script, narration, or copy evoke sense and place:

- The sound of kookaburras at dawn.

- Red dust in the boot of your car.

- The way wind moves through a silo at dusk.

- The smell of eucalyptus smoke at a night market.

These details anchor emotion in place—turning a story into an embodied memory.

Trust Local Voices

Professionally scripted content can polish a message—but raw, real, locally spoken stories build trust.

Fund community storytelling projects. Offer small grants for locals to make audio pieces, short blogs, or narrated videos. Involve schools, Elders, or local artists.

You’re not just making tourism assets—you’re investing in place identity.

Match Story Medium to Story Mood

Not every story needs to be video. Some stories are best as slow-burn essays. Others shine as photo essays, spoken-word audio, or print.

Let form follow feeling:

- Use video for emotional journeys and sensory immersion.

- Use audio for voice-led reflection or cultural story-sharing.

- Use text for introspective, character-rich narrative.

- Use interactive maps to let visitors follow a story trail.

Tourism is no longer just about physical access—it’s about narrative accessibility.

Make Narrative a Strategy, Not Just a Campaign

Too often, storytelling is treated as a marketing extra. But when integrated into tourism development, it can align:

- Economic growth,

- Cultural preservation,

- Community inclusion,

- Environmental stewardship.

Councils can embed narrative thinking into everything from grant programs to signage, wayfinding, and stakeholder partnerships.

Because the most powerful regional brands don’t just show their story—they live it.

The Benefits of Narrative-Driven Tourism

Stories don’t just attract attention—they shape perception, memory, and trust. And in the tourism space, that leads to measurable outcomes.

For regional Australia, where destinations often compete with each other and against entrenched stereotypes, narrative transportation is a way to differentiate not by scale, but by emotional connection.

Here’s what the research—and the results—show:

Increased Visitor Intent and Emotional Recall

Psychological studies have shown that audiences who experience narrative transportation—who feel emotionally immersed in a story—are more likely to:

- express intent to visit,

- remember details about the destination,

- and share the story with others.

In other words: a well-told story travels further and lasts longer than any itinerary or discount offer.

Campaigns like Tourism Tasmania’s “Off Season” saw significant engagement increases because audiences weren’t just informed—they were moved. When a place makes people feel something, it creates mental shelf space.

Stronger Word-of-Mouth and Social Sharing

Emotionally resonant stories are stickier. They get retold.

Whether it’s a video, a podcast, or a written piece, narrative-based campaigns often outperform traditional marketing on:

- video completion rates,

- organic shares,

- and unsolicited re-posts by visitors and locals alike.

This effect is amplified in smaller communities, where pride and participation are high. Locals are more likely to share stories they see themselves in—and that turns every resident into a low-cost brand ambassador.

Visitor Satisfaction and Deeper Engagement

When visitors arrive already connected to the story of a place, they:

- stay longer,

- explore more deeply,

- and report higher levels of satisfaction.

They don’t just come for photos—they come for experiences aligned with a narrative. They’re looking for the potter they read about, the paddock-to-plate chef they saw on video, the place in the story where something quiet and meaningful happened.

Long-Term Place Repositioning

For regions struggling with outdated or reductive schemas—“sleepy town,” “past its prime,” “off the map”—narrative strategy can lead to gradual but lasting perception change.

New Zealand’s “100% Pure” campaign didn’t just boost tourism. It changed how the world saw the country—as a cinematic, mythic, and cultural place worth knowing.

This repositioning matters not just for tourism, but for:

- inward migration,

- creative industry investment,

- indigenous economic development,

- and regional pride.

Narrative is not just marketing. It’s reputation infrastructure.

Challenges and Pitfalls to Avoid

While narrative storytelling offers powerful tools for regional tourism, it’s not without risk—or resistance. The most emotionally resonant stories often require letting go of control, allowing complexity, and embracing a slower, more relational form of communication.

Here are some of the most common pitfalls councils and tourism teams face when working with narrative frameworks like transportation theory:

Confusing Promotion with Story

Many campaigns say they’re “telling stories,” but what they’re really doing is showcasing products or summarising facts. A story isn’t a list of attractions. It’s a journey. It has a point of view, tension, and transformation.

Avoid: videos that simply rotate through experiences without a throughline or human anchor.

Instead: build your story around a character, a mood, or a question that needs resolving.

Over-scripting and Under-belonging

Authenticity can’t be faked. Highly scripted content—especially if it’s voiced by actors or written in generic tourism copy—often feels hollow. Locals may not see themselves in it. Visitors won’t believe it.

Avoid: polished but emotionally flat content.

Instead: fund stories told by real locals, in their own voice and cadence. That rawness is often what makes them memorable.

Fear of Specificity

Many regions try to be all things to all people—appealing to young families, digital nomads, grey nomads, foodies, adventurers, artists. But the best narratives don’t generalise. They go deep into one moment, one experience, one truth.

Avoid: messages like “something for everyone” or “a little bit of everything.”

Instead: tell one really good story and let the audience find themselves inside it.

Lack of Narrative Infrastructure

One-off stories—even great ones—won’t change perception alone. Narrative transportation is most effective when there’s an ecosystem: signage, local guides, accommodation hosts, regional branding, and event programming that all speak the same emotional language.

Avoid: treating story as a campaign layer.

Instead: embed it in your broader regional development strategy—from creative funding to visitor experience design.

Short-Term Thinking

Storytelling is a long game. It may not deliver immediate ROI on ad spend—but it can create lasting shifts in how a place is understood, remembered, and talked about. Councils need to resist the pressure to deliver “quick wins” and commit to slower, layered narrative building.

Avoid: short seasonal campaigns with no follow-up or continuity.

Instead: build narrative arcs over multiple years—deepening character, broadening themes, and allowing community voices to evolve.

These challenges are real. But they’re not reasons to avoid narrative work—they’re reasons to approach it with care, collaboration, and integrity.

When done well, storytelling doesn’t just change what people see—it changes how they feel. And that’s what turns casual visitors into lifelong advocates.

From Storytelling to Story Stewardship

At its core, narrative transportation isn’t about content—it’s about connection.

It’s what happens when someone in a Melbourne apartment watches a short video from Alice Springs and, for a moment, forgets where they are. When a visitor hears a farmer-turned-brewer tell their story and decides to stay an extra night. When a local sees themselves reflected in a campaign and feels—perhaps for the first time—that their town matters.

This isn’t marketing gloss. It’s cultural infrastructure.

For regional Australia, where perception can be as limiting as distance, story offers a bridge. Not just to visitors, but to new narratives of identity, community, and economic resilience.

So the task for councils and tourism boards is not just to tell better stories—but to become story stewards:

- Create conditions for local stories to be heard.

- Invest in narrative capacity, not just creative services.

- Align storytelling with cultural, ecological, and economic goals.

- Let emotion, specificity, and voice lead the way.

The regions that will thrive aren’t necessarily the ones with the flashiest footage or biggest budgets. They’re the ones who can invite the world in—not just to see their place, but to feel it.

Because in the end, it’s not the information that moves people.

It’s the story they want to step into.